A King in Hiding Read online

A KING IN HIDING

Originally published in French in 2014

by Éditions des Arènes

under the title Un roi clandestin

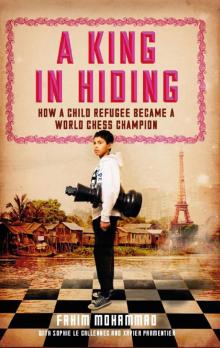

A KING IN HIDING

HOW A CHILD REFUGEE BECAME A WORLD CHESS CHAMPION

FAHIM MOHAMMAD

WITH SOPHIE LE CALLENNEC AND XAVIER PARMENTIER

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY BARBARA MELLOR

Published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE,

Suite 101, Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in Canada by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

ISBN: 978-184831-828-1

Original text copyright © Éditions des Arènes, 2014

This translation copyright © Barbara Mellor, 2015

The authors have asserted their moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher

Typeset in Adobe Text Pro by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

CONTENTS

About the authors

Prologue

1. The chess player

2. Life was good

3. My life is over

4. An endless journey

5. Welcome to France

6. A true discovery

7. Spring, summer, setback

8. My secret dream

9. Everyone’s convinced

10. Life on hold

11. Castles in Spain

12. Just a single pawn

13. Endgame

14. Case by case

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Fahim Mohammad was born in Bangladesh. At the age of eight, he had to flee with his father to escape a threat of abduction. They journeyed across Asia and Europe and eventually settled in France. While they struggled to make a life for themselves as illegal immigrants, Fahim, already a keen chess player, was talent-spotted by Xavier Parmentier, who took him under his wing and trained him for competition. In 2012, Fahim won the French national Junior Chess Championship. In 2013, he won the World School Chess Championship Under-13 title.

Sophie Le Callennec is an anthropologist and expert in East African geography, and has written numerous school textbooks. She taught French to Fahim’s father, and lent her pen to their story.

Xavier Parmentier is a Master of the International Chess Federation (FIDE) and a renowned professional coach in France. He has coached the national junior chess team for twenty years. He is currently Director of Training for professional coaches within the French Chess Federation. He is personally involved as a volunteer coach for young talent in chess clubs in the Paris suburbs.

Barbara Mellor has 30 years’ experience as a translator and editor, specialising in art, architecture, history, fashion and design; her translation of Agnès Humbert’s wartime journal, Résistance: Memoirs of Occupied France (Bloomsbury, 2008) received widespread praise.

PROLOGUE

On 4 May 2012, two days before the second round of the French presidential elections, prime minister François Fillon was the guest on the phone-in segment of the France Inter morning radio show. A caller rang in to raise the case of a young boy of eleven who had just been crowned French national chess champion. The boy was a homeless asylum seeker whose appeal had been refused, who was living in hiding with his father in the Paris suburb of Créteil, in constant fear of deportation. The affair had attracted media attention over recent days, and it had caused a considerable stir. In response, François Fillon promised live on air that he would look into the boy’s case. Within a few days it had been settled.

The boy’s name was Fahim. At the point when his story started to attract attention, I was living in Créteil. I knew his father, as I had been part of the support network that had grown up around them. I had known Xavier, his chess master, for ever. When it came to writing their story, it seemed natural for them to turn to me: to listen to Fahim, to express his thoughts, interpret his silences and be at his side throughout the writing process.

I could not have imagined how close we would become over those months spent together. How often Fahim would come to my house, where I live with my children. How in addition to telling the story of his past, he would also ask for my help in building his future.

This is the story of a small boy who used to live in a distant land, a good little boy who was loved, and who – like all children of his age – spent his days playing and daydreaming. Until the world of grown-ups decided otherwise.

This is the heartbreaking story of how, at the age of just eight, he was forced to leave all this and to flee his country, to seek refuge far away from his home and his loved ones. Of how his world damaged and destroyed him until he managed to snatch the right to live a normal life. It is also the story of how he encountered a remarkable man. It is a tale of modern life from which – largely thanks to this man – hope and solidarity emerge triumphant.

I have written this book with Fahim. The words and feelings are his. I give them to you. And I give them back to him.

Sophie Le Callennec

For my father

For everyone who has helped me and everyone who continues to help me

Fahim

Chapter 1

THE CHESS PLAYER

My father was good. Very good. He was always playing chess and he always won. At home he played for hours. Several times a week he went to the chess club and stayed there late into the night.

There were chess sets everywhere in our house. Boards of all sizes, pieces in all shapes, and books on chess. A world in black and white. When my father played chess with his friends, I would sit and watch: I said nothing, understood nothing. Afterwards, I would race outside to play with my friends.

One day when I was five, my father said:

‘Would you like to come to the club with me?’

He’d never taken me with him before. I was a bit worried that it would be boring, but I said yes. I was proud. We crossed Dhaka to reach an impressive building in the banking district. At the end of a long passage lined by men smoking and talking, we came to a big room full of people. Everyone knew my father and said hello to him, then they asked my name or if I would like a drink.

When they started to play, the atmosphere became serious and the heat pressed down. The players made their moves at top speed. They tapped on the clocks beside them and made all sorts of other clicking and rapping noises. I could hear little yelps, sometimes of surprise, sometimes of joy or despair. It was all very different from the quiet way my father played at home. To begin with it was fun to watch, but soon I got bored. I didn’t dare to disturb

my father, so I sat on a chair, swinging my legs, and waited.

A man came up to me:

‘Would you like me to teach you?’

I didn’t dare disappoint him.

‘Yes …’, I whispered.

He went off to fetch a large wooden board, put pieces on it one by one, according to some mysterious rule, and started to explain. I listened, but it was complicated. So I said nothing and stifled my yawns so as not to be rude.

Back at home, I thought about chess. The thoughts went round and round in my head and got all muddled up, but I wanted to understand it. I asked my father about it, and he was surprised: it was obvious to him that the game didn’t interest me. But I wouldn’t give up, so he set up a chessboard on the low table in the living room and I tried to memorise where the pieces went. He introduced them to me:

‘This one with the cross, is the “king”, and this one with the crown is the “queen”. These are the “rooks”, “knights” and “bishops”.’

‘Why do they have English names?’

‘Because the British colonised Bangladesh and taught us how to play in their language.’

They looked funny and made me laugh.

The next day I tackled him again:

‘Abba [Dad in Bengali], what do the rooks do?’

My father explained, showing me how the pieces move and teaching me how you capture your opponent’s. Between the king who moves one square at a time, the queen who can cross the board in one go and the pawns who move forward one or sometimes two squares but take other pieces diagonally, it was really complicated. But exciting. So I asked more questions, the next day and the day after. More and more, over and over.

‘Abba, how do the knights move?’

‘Abba, how does the king capture other pieces?’

‘Abba, which is stronger, a rook or a bishop?’

Patiently, my father would explain it all to me, putting me right and encouraging me. Then after a while he would stop with a sigh and promise me:

‘Tomorrow we’ll see if you’ve got it clearer in your head.’

The next day we would start again. My father would teach me how to defend my pieces, show me how to scare my opponent. I loved chess, but inside my head it was all a muddle. I made stupid moves. I was no good. My father knew it. He must have done. Because every time he ended up heaving a sigh and stopping:

‘OK, Fahim, we’ll carry on tomorrow.’

Maybe chess was just too difficult for me. Maybe I was the worst chess player in the world. Too bad! I carried on. I wanted to understand. I was determined to get better, however long it took.

One day, my father showed me a trick for surprising my opponent and trapping his king. All of a sudden, the chessboard came to life: the pieces jumped up and stood in rows, the rooks headed straight for the enemy camp, the bishops zoomed to and fro, the knights leaped about all over the place, the pawns obeyed unquestioningly, even when their orders meant risking their own lives in order to free a senior officer who’d been taken prisoner by the enemy; the king, weak, slow and almost insignificant, was as docile as a baby, and begged me to save him from death; and the queen, my queen, strong, quick and clever, pirouetted around the board, dominating the fight.

It wasn’t a chess match any more, it was a battle. It wasn’t a game, it was war. I mustered my troops, sent out messengers, set traps, decided who to keep and who to sacrifice, protected them and led them to victory.

It was a week since I’d started to learn, and now I understood: I could play!

Chapter 2

LIFE WAS GOOD

XAVIER PARMENTIER: I’m a chess master. I’ve taught chess for over 30 years now. Before I met Fahim and he became my pupil, I could locate Bangladesh on a globe, sharing a border with India. I knew it was one of the world’s poorest countries, but I wouldn’t have been able to tell you that its capital was Dhaka. And I didn’t know either that it is so much at the mercy of typhoons, cyclones, tsunamis and floods that by the end of the century, unless we do something to halt climate change, it will be swallowed up by the oceans.

It was when I began to take an interest in Fahim that I started to really find out about this country where he was born and spent the first eight years of his life: a country smaller than Tunisia with a population larger than Russia, where one child in five suffers from malnutrition even before they are born. And before this little guy turned up at the club that I ran, I would certainly never have associated Bangladesh with the world of chess. It didn’t take me long to realise that Fahim was very different from our usual image of immigrants from developing countries. He didn’t live in a shanty town in Dhaka, and he wasn’t a street kid, roaming the dusty highways and dodging cars and cycle rickshaws to beg a few coins from passers by who didn’t care. He hadn’t left his country to flee poverty. Quite the reverse, in fact: he came from a middle-class family who, without being exactly wealthy, nevertheless lived a life that was tranquil and free of troubles.

My father was a fireman: he saved people’s lives. When there was an accident, he used to go off in the red truck with the siren blaring. When there was a fire, he would put it out. When someone was drowning, he would dive into the river to save them.

In the evening, he used to tell us stories about the people whose lives he’d saved, the tragedies he’d prevented. And then there were the times when he couldn’t help, like the story about the man who woke up in the middle of the night to find his house was on fire, and who was so poor that his first thought was to save the only thing he owned, his television. When he went back in to save his sons, it was already too late: the building had gone up in flames, with his children imprisoned inside. He stood there watching. He howled and wailed. Then he picked up his television and hurled it into the flames. My father also told us how his commanding officer had sacked him from the ambulance team because he’d refused to demand money from a very poor woman who had to be rushed to hospital because she was having a baby.

Then my father got old: he was over 40 and he retired from his job. He didn’t save people’s lives any more, but he went to the barracks every day because we lived nearby, because he was friends with the firemen, and because he liked looking after the garden there. And he had a new job: he set up a car hire company. The rest of the time he played chess. He and a friend started a chess club. People poked fun at first, but then they stopped: it was a very good club and it became famous.

We were rich. We lived in a big house with two rooms: a bedroom with a double bed for me and my sister, and the living room, which had my parents’ bed in the corner. And the baby’s bed too.

It was a lovely house, but it needed a lot of repairs. One day, a great chunk of ceiling came down right beside me and scared the life out of me. Cyclones were frightening too: it felt as though the wind was going to tear the walls apart. It wasn’t just me who got worried either: our neighbours would come to our house and say prayers in Arabic. The monsoon season didn’t bother me though. The rains were torrential, there was water everywhere and everyone got fed up with it, but it wasn’t frightening. When the courtyard turned into a lake, the neighbours would pile up sandbags so they could walk about without getting their feet wet. Sometimes the water would come up over the steps and into the house.

I knew we were rich because my father was the only one in our family – in our whole neighbourhood – to buy a cow for Eid: everyone else just had sheep or chickens. I would lead the cow home and my father and a friend would cut its throat. The blood would spurt all over the place, but I was used to it. What I didn’t like was the look in the cow’s eyes as it died: I could see it was afraid. Would it be the same for a person, I used to wonder?

On the day of the feast, my mother and father would prepare food for everybody: family, neighbours and firemen. My mother’s cooking was so good that everyone wanted to come and share with us. So she would spread the floor with big cloths of all colours for our guests to sit on. Then we could dig in. What a spread!

I

liked everything about my life. Except for school. In the morning my parents would shake me awake, gently at first, then more roughly. In the end I would get up, but I was always in a bad mood. I wouldn’t speak until I got to school. As soon as I was back with my friends again I would feel better.

I spent my first year in a school where the lessons were too easy. I was always top of the class. So my parents sent me to a private school that was very expensive. I was a good pupil and did as I was told. I didn’t have much choice. In Bangladesh the teachers were strict: if you didn’t work, they hit you with a stick. There were 70 of us in my class, and we all took turns to get beaten. Or all the boys did, anyway: the girls used to work hard and never got beaten. One day the teacher hit a boy so hard that he had to stay at home for a week while his wounds healed.

Like all the others, I went to school in the morning and studied with tutors in the afternoon. Some of the children in my class cheated, and had private lessons with teachers from the school, so that they would know what to revise for the tests. The tutors my sister and I had didn’t know which topics were going to come up, so they would make us do our homework and then give us more. When it was time to pray, I would sometimes tell them I had to go to prayers and then run off and play with my friends.

There was a shared courtyard in front of our house where we used to play cricket, and sometimes badminton. There was a big tree with branches that got in the way, but no one could remember who it belonged to: the neighbours argued about who planted it, and unless they could agree no one could cut it back. When we got fed up with the tree, my friends and I would go off to find other places to play. When I was little, we used to go swimming in the lake. But then it got all dirty and overgrown, with snakes lurking in the tall grass, so we stayed away, even when the heat was suffocating. We would roam around to other places, along the path behind the firemen’s barracks or in front of the mosque. One time, our parents came out looking for us everywhere. When he found me my father was furious, with big black angry eyes. He told me I had to stay either in the courtyard or at the barracks.

A King in Hiding

A King in Hiding